The five key challenges for theological education in developing countries

Author: Martin Olmos

Last Updated: 16-Mar-2016

Our vision is to develop an effective way for christians in developing countries to learn how the Bible fits together, with Jesus and his gospel of grace at its heart. From the start of this project, we've been aware of how we need to understand the need and challenges very deeply in order to design an effective solution. We also appreciate how different the lives of christians in developing countries are to our own, so we have involved several people from this context into the design process. We have therefore done a lot of research, interviewing dozens of people in a range of roles related to biblical education in developing countries: Bible college principals, missionaries, pastors, donors, and lay christians. We've put much effort in understanding the need very clearly.

Challenges

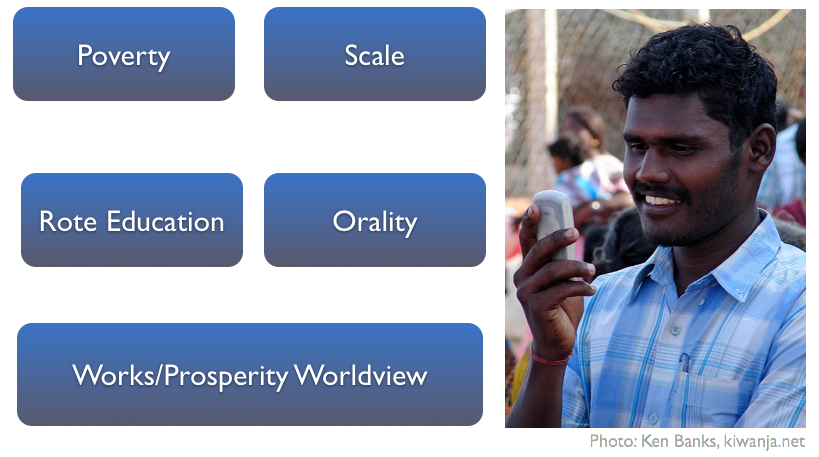

Through our many interviews, five themes kept coming up as challenges that made it hard for christians to learn the Bible well. We have designed a framework that describes these five challenges and how they interact, which has been well received. We describe it below, together with a specific scenario. The five challenges are:

The challenges that christians in developing countries face in knowing the gospel of grace are their:

- poverty, which limits their access to most things, and while there is a longing to get ahead from their hard life, formal education is often out of reach.

- large numbers, which make formal, traditional education impractical to deploy.

- orality, which gives them limited access to God's written Word.

- rote education, which hasn't trained them at reading the Bible deeply for themselves.

- works/prosperity worldview, often flowing from an animistic background which seeks to control the spiritual through payments, ceremonies, special words and charms and thus takes grace away from the gospel.

Poverty

Christians in developing countries have low incomes - this is the most obvious challenge. They can't afford current formal course offerings. However, their incomes are also unpredictable. It is hard for them to plan more than a few weeks ahead, as they don't know . Indeed, many live week to week or even day to day. Additionally, most are time poor as well as financially poor. Things that westerns would consider basic, such as transport or getting water, take much longer. Attending a course often involves travelling to another place, taking time away from home chores and paying jobs. Enrolling into a formal course with an upfront fee which commits the student over several months in the future would typically not even be a consideration. Education is seen as a pathway out of poverty, and a credential is valued highly. However, the 'first step' is too high for most.

Dini is a 22 year old mother of two young children, living in Korogocho, a large informal settlement in Nairobi, Kenya. Her family earns about $3-5 per day, depending on how much work her husband finds. Rozi's family live in a single room made of stick and mud with an iron sheet roof. Her husband currently has some work as a truck driver and is often away. Dini tries to make a bit of extra cash selling at a nearby street corner. She has little time to spare. Something as simple as getting water involves a 40 minute return walk and wait at the local pump. She has a mobile phone that can SMS, play music and video, and even access the internet - although that's very expensive for her. It was a big expense, but she depends on it for many helpful things. Dini and her husband would love to complete a course with a certificate that would open new opportunities to them, but the current options cost too much in money and time. Entertainment such as radio and TV let her escape her hard life for a little while.

Scale

The size of this population is very large: there are 400-500 million evangelicals in Africa, Latin America, and Asia1. While the church's growth has been wonderful, it is also tragic that so many don't have access to good biblical training that suits them. The church's rapid growth has raised the need for strong and well-trained leaders as well as good discipling and training resources for lay christians. Subsidising current formal education for some is helpful, but it is not feasible to serve all christians with traditional formats.

Korogocho, where Dini lives, is a big place: between 150,000 and 200,000 people live there. Kibera, where Dini's sister lives, might have up to a million people, but it's hard to say. Dini attends a large church of close to 500. It only has one pastor, and he needs to supplement his income with another job. He has completed primary school, but has no formal theological education. He does the best he can, but wishes there were resources that would help him teach the Bible well. A few aid agencies are involved in Korogocho, but they are overwhelmed with the need.

Rote Education

This refers to a culture of being given the answers by the teacher, and then simply repeating them when asked. The teacher is the authority and source of knowledge, and asking questions can be seen as questioning their authority or bringing shame on their abilities. Critical thinking , asking questions, and learning from first principles to come to a deeper understanding is not taught or encouraged. This was a common challenge brought up by missionaries. Although God gifts his church with teachers that we submit to, we are also to weigh up their teaching with discernment, with the Bible as the standard. When christians are not taught to read the Bible for themselves, they are vulnerable to fall into misunderstandings. Further, the Bible's teaching is likely to be taken at a superficial level only, rather than letting it deeply transform the whole of life.

Dini completed five years of primary school. She remembers repeating the teacher's words, even though she often didn't really understand. At church, she listens to her pastor but often doesn't understand. She is ashamed and a little afraid to ask her pastor - she doesn't want to offend him. She knows several Bible stories well, but she's not sure what to make of them in her own life. If asked 'does God save us by grace?', she knows the answer is 'yes', but she hasn't really understood deeply what that means in her daily life - she still feels she needs to earn God's blessing and has consulted a shaman when things were particularly hard. There is no small group where she might discuss the Bible, mostly because there are no qualified leaders. She has no confidence in reading the Bible for herself. She often listens to preachers on the radio who seem to say different things than her pastor, but has no way of discerning between them.

Orality

Most christians in developing countries don't have a strong 'reading culture': learning by reading and even reading for leasure are uncommon. Rather, they have a strong preference for learning orally through stories and drama. Concrete thinking and discussion is preferred over abstract concepts. Orality is not the same as illiteracy: many oral learners will have some basic literacy level. Further, orality is a cultural dynamic rather than merely a skill, and so cannot be addressed with just literacy training.

Dini has basic literacy: she can read signs and basic instructions, and she texts her sister a lot. However, she hasn't read a book in years. None of her relatives or friends would read a book or the newspaper for entertainment. She listens to the radio, and enjoys music and short video clips on her phone. She often shares these files with friends via Bluetooth technology. She likes the idea of doing a course to get ahead and grow, but she feels threatened at the thought of all the reading involved.

Works/Prosperity Worldview

A common worldview is that God blesses those who are 'good enough', leading to the understanding that the rich are good enough for God's blessings but the poor must be under God's curse. Its focus is on getting God's stuff rather than God Himself: a personal, intimate, and loving relationship with our creator. This is reinforced by a background of animism which seeks to control the spiritual through payments, ceremonies, special words and charms. Jesus becomes merely a tool for gaining what our worldly heart desires, rather than gaining a new heart that desires God over his stuff. It promotes a trust in our own efforts, rather than a trust in Jesus as God's chosen rescuer of humanity. It takes grace away from the gospel. This is the deepest challenge. As with Western christians, christianity can too often be a veneer over a deeper set of beliefs (e.g. paganism or animism) which really drive a person. Christianity can be kept in a box for Sundays without affecting the rest of life - especially in the absence of good discipleship.

Dini often wonders why her life is so hard, when she hears that God is good and full of blessing. Dini grew up with some animist practices in her family and developed a deep sense of the need to pacify spirits for life to go well. She also hears preachers promising success in this world, if she only has enough faith. She can't help thinking that God has something against her, and wonders what she must do to gain his favour.

How they interact

Although each of these is significant on its own, the five challenges combined, together with the interactions between them, present a formidable task. We have laid these out in this way intentionally, with increasing difficulty and complexity from the top down. We see three dimensions to the needs: economic, educational, and core beliefs.

Poverty and Scale form the economic dimension to the need. Individually these are the 'easiest' challenges to solve because mere money would go a long way to address them. However, when combined, the two make it hard to address this dimension sustainably. Poverty means that christians can't afford traditional offerings, and scale means Western organisations cannot afford to subsidise them for all.

Rote Education and Orality form the educational/learning dimension, as they affect the way christians learn. Combined, they make it hard for lay christians to read the Bible for themselves and learn its great truths from first principles. Sadly, this can leave them vulnerable to unhelpful and false teaching. Further, it makes it harder for them to reflect on how these truths impact on their whole lives: marriage, money, parenting, work, etc. This can lead to Christianity being adopted at a superficial level.

Works/Prosperity Worldview forms the 'beliefs' dimension, the most fundamental challenge. In combination with the 'rote education' challenge, it means that even someone doing a theology course might learn more facts about the Bible without touching this worldview.

Opportunities

Although these seem huge challenges, we also see several exciting opportunities:

- Church growth: The growth in the church over the last few decades has been simply astonishing. There is a recognised need for discipleship and Bible teaching resources.

- Economic growth: Millions have been lifted from abject poverty (although naturally much progress is still required). For example, inflation-controlled GDP per capita in sub-Saharan Africa has tripled since 20002. This creates a growing aspirational class, for whom education is a valued service. C. K. Prahalad has argued convincingly that low income populations can offer sustainable markets, when the product or service is designed specifically for them3.

- Younger demographics: Over 41% of Africans are under 15 years old4

- Mobile broadband: Access to mobile phones has exploded in the developing world, with penetrations well above 90%. About one in three people in developing countries are already online, and improving fast. Two third of all people online live in developing countries. Online access comes via cheap Android smartphones with larger screens, web access, and multimedia support, which are also growing very fast. Although data charges are very expensive for the local population, this is likely to drop in the near future. As a specific example, in India, "every second three more Indians experience the internet for the first time. By 2030 more than 1 billion of them will be online."5 Myanmar, where we are trialling, is an interesting setting because Its economy has opened recently, and so the mobile phones are new and with higher specifications.

Our Approach

Clearly, these five challenges and four opportunities call for a radical approach. At the same time, the opportunities frame promising approaches. Traditional educational formats used in the Western world were designed for a very different audience: wealthy, highly literate, well trained in critical thinking and Bible reading, and generally taught the gospel well. Therefore, traditional Western approaches will find it hard to help lay christians in the developing world facing these challenges. We have designed our drama from scratch for this particular audience, with their own needs and context.

Our Bible teaching drama could be distributed free or at minimal cost, at huge scales. It helps rote-educated oral learners to think deeply and consider the text for themselves. Lastly, it uses the power of drama to speak to deep beliefs. Below we outline how each challenge is addressed:

- Poverty: Free access to the material, with an option of a credential for a low fee, in the range of the cost of a coke at a local kiosk. The credential would be charged on a per-lesson basis, paid weekly as the lessons are completed. It is totally flexible to cater for the volatility of poverty. It is very lean, to minimise mobile charges, and can be freely shared once downloaded.

- Scale: Able to serve hundreds of thousands, or even more. It can be broadcast on radio or downloaded from basic feature phones. We have designed our web app to allow for free sharing of the audio without internet access. We've modeled costs into hundreds of thousands. Our model affords access to the material at huge scale without significant support costs.

- Rote Education: An informal drama, without a formal teacher role, and it puts the audience in the middle of engaging dilemmas between contrasting model characters, so the audience must think through it. The lessons encourage discussion in a small group, encouraging reflection rather than simple repetition of an answer.

- Orality: Entertaining and relevant story dealing with concrete situations illustrating abstract truths. The simple dramas can be enacted as part of the learning process.

- Worldview: Uses the power of drama to contrast God's way of grace with our own way of works, to challenge and transform deep beliefs through the deep emotional bond with the protagonist.

We have also designed our offering to take advantage of the opportunities. We aim to work with churches and their leadership, so that the church can grow together and the leaders can also be helped to develop further. We want to offer a pathway to more formal biblical education for the growing aspirational population coming out of poverty. Our drama will cater for a younger audience through its characters and situations. Lastly, it relies on mobile phones as the platform that this audience has access to.

We're not saying there is anything 'wrong' with either the current educational offerings or with the audience for this project. Under God's kindness, and with considerable efforts by both Western and Global South christians, these offerings have blessed many. We're simply noting that there is a mismatch - it's a huge challenge for the typical lay christian in a developing country to get the most from current offerings.

What do you think?

We appreciate that these are broad generalisations, and that there is wide variety within countries, let alone the whole developing world. We are not putting ourselves forward as experts, but simply sharing what we have learnt so far. We have reflected on how Western christians can also put a christian veneer over a materialism or consumerism worldview. We also think that we are all oral learners and find stories a powerful way to learn, especially when it comes to challenging deep beliefs and worldviews. It is only through the gift of extensive quality education that we can develop our literacy skills, which help us think more abstractly.

We are keen to understand the need well, so we can develop a solution that will be helpful. We want to learn more from your experience and reflection. What have we missed or overstated? Please email us (details below) or sign up for updates.